When the lightness comes, I notice it feels good.

But an old part of me—an ancient part of me that dislikes the unfamiliar company of the lightness—wakes up and tries to kick it out.

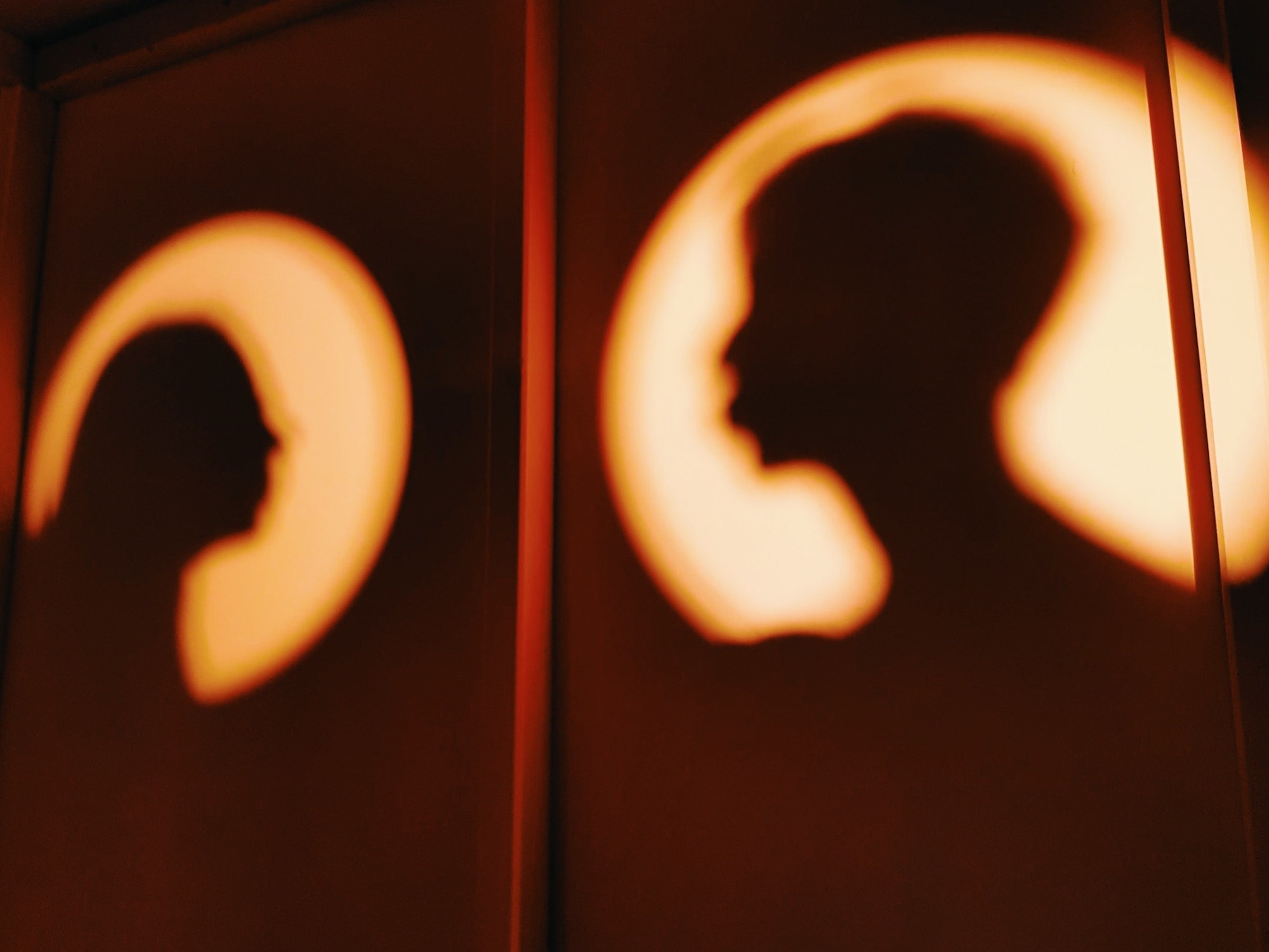

Meet Lee & June

For our purposes here, I’m going to give these two characters names. Let’s go with Lee for lightness…because that’s some irresistible alliteration. And, I’m going to call that old part of myself June.

June (old part of myself) hates that Lee (lightness) exists. Plain and simple, June wants Lee to fuck off.

Yes, June recognizes that Lee makes life pleasant. In fact, Lee is a breath of fresh air compared to the heavy weight of eight years of low-level depression.

However, that heaviness is all that June knows. She loves it. The heaviness—and the equally heavy negativity that comes along for the ride—is familiar. It is comfortable. It is safe.

So, when Lee walks in on a cloud, June freaks out because the familiar, comfortable, and safe heaviness and negativity start to disappear.

Lee upsets the order.

At its core, June’s freak out is about protection and survival.

Lee is unfamiliar, and because she’s unfamiliar, June must use what survival skills she knows (fight, flight, freeze, negative self-talk, etc.) to get Lee out of the picture.

This feud between Lee and June happened to me—has been happening to me—as my long-term relationship with depression dissolves and I find space to hesitantly dip my big toe into the waters of childhood trauma.

When the Lightness Comes and I Don’t Want to Tear Myself Down

I feel lightness.

I think other people might describe the lightness I feel as contentment, ease, calm, peace, and maybe even happiness.

That last one is a stretch though. For now, I can accept low-level happiness. Because, if I can have low-level depression for eight years, I can have low-level happiness for a few days.

Anyways, the lightness is new to me. I want to love it. I want to accept it, but I’m afraid.

As I observe the lightness (Lee), as I notice how good it feels, an old part of me (June) wakes up and tries to drive the lightness out because this all boils down to familiar versus unfamiliar.

That old part of me is trembling with fear and desperately wants to use survival skills to protect me from the unfamiliar. But, June’s survival skills are splintering, clumsy, and misshapen. My whole life, June protected me the only way she learned how—by tearing me down. That is the familiar way of doing things. That is comfortable. None of this lightness, low-level happiness nonsense from Lee.

But, with this lightness here, tearing myself down doesn’t make much sense to me anymore. It doesn’t feel right anymore.

The tearing down—whose idea was that again?

Brief aside. Over the holidays, I saw The Favourite. When the movie ended, a man in the row in front of me asked his family whose idea it was to see that movie.

Good question.

If you want to experience how an art form can thrust discomfort upon you, see The Favourite. If this sounds like a panic attack waiting in the wings, stay home and watch Frozen.

Let’s get back to it, shall we?

Take a deep breath.

I was writing about—and you were reading about—how, in the presence of lightness, I started to see cracks in the foundation of my go-to, fucked-up way of protecting myself, i.e., tearing myself down with nasty, negative self-talk.

And, I was wondering about the origins of my nasty, negative self-talk, too.

Getting Nasty with Negative Self-Talk

What is this nasty, negative self-talk?

Well, if we must.

I don't deserve to feel good.

I don't deserve lightness.

I don't deserve low-level happiness.

I don't deserve [insert "positive" thing here].

I hate myself.

I want something bad to happen to me.

I want to erase myself.

These words have kept me alive. They have kept me going. Yes, even the “erase myself” one, oddly enough.

They have kept me alive, kept me going until very recently, that is, because I’m different now. I don’t want to be undeserving. I don’t want to hate myself. I don’t want to wish the worst upon myself. And, I don’t want to erase myself.

Dare I ask it, but…do I like myself?

Enter Dialectical Behavior Therapy: Using “Check the Facts”

There I was with an itch to scratch. I needed some answers:

- Why do I have this nasty, negative self-talk?

- Where did the nasty, negative self-talk come from?

- Why is it so automatic?

- And why does it feel comfortable, good?

That’s when I decided to turn to my trusty sidekick dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) and a skill called “check the facts” to explore my negative self-talk.

“Checking the facts” on my negative self-talk provided perspective. I realized that these thoughts come from fear and a survival instinct. In fact, I think that my thoughts would stretch into the most painful of places if only it meant my safety and survival.

Fear and survival instincts breed desperation. Hence, the Donner party.

But alleged cannibalism aside, I started to wonder that if my thoughts come from fear and survival, then I don’t have to listen to them, right?

Yes…and no.

No, because you have some exploring to do, girl.

No, because there are reasons why these thoughts wield power, there are reasons why I connect with them, why they feel like a big, steaming mug of hot cocoa, a soft teddy bear, Linus’s blanket, and [insert warm, fuzzy thing here].

A Five-Year-Old’s Guide to Survival

– Liz Lemon

Image: Amy Reed

When I was a kid, maybe around five-years-old, I remember sitting on the toilet in a pukey, mint-green-colored bathroom stall and, in as private a moment as you can have in the girls’ restroom at a public elementary school, I remember starting to spin this narrative, starting to use those words of not deserving to feel good, of hating myself, and of wanting something bad to happen to me. I was still too innocent to contemplate erasure, so at least I spared my sweet five-year-old self that mortal anguish, huh?

That’s how five-year-old me survived. And, unfortunately, I never learned a different way to cope with life. So, for 25 years, I clung to my narrative for dear life.

Yes, this survival strategy is maladaptive. It is ineffective. And, it really, really fucking hurts.

But, I remind myself that it was the best that I could do at age five.

So, gold star?

Survival Skills, A.K.A. Character Adaptations, A.K.A. Traumatic Adaptations

The survival skills we build as children, whether healthy or unhealthy, that we continue to use as adults, are character adaptations (thank you to a certain psychiatric nurse for this gentle term). As children, and as any creature young, old, or otherwise, we desperately pull out all the stops to figure out how to adapt to our environments.

If you’re lucky, you create healthy character adaptations.

If you’re a kid growing up in an adverse environment, you can create healthy adaptations, but you face an uphill battle waged with no body armor, no shields, no weapons, and you probably aren’t wearing shoes either.

I’m not a fortune teller, but more likely than not, adverse environments push children toward ineffective character adaptations. I am a bright and shiny case in point.

But, don’t take it from me, especially because I’m not an expert. Rather, let’s find out what Bessel van der Kolk has to say on the subject.

We all know what happens when we feel humiliated: We put all of our energy into protecting ourselves, developing whatever survival strategies we can. We may repress our feelings; we may get furious and plot revenge. We may decide to become so powerful and successful that nobody can ever hurt us again. Many behaviors that are classified as psychiatric problems, including some obsessions, compulsions, and panic attacks, as well as most self-destructive behaviors, started out as strategies for self-protection. These adaptations to trauma can so interfere with the capacity to function that health-care providers and patients themselves often believe that full recovery is beyond reach. Viewing these symptoms as permanent disabilities narrows the focus of treatment to finding the proper drug regimen, which can lead to lifelong dependence—as though trauma survivors were like kidney patients on dialysis.

The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma by Bessel van der Kolk

Agreed.

Knowing how much energy the sheer act of survival requires keeps me from being surprised at the price [trauma survivors] often pay: the absence of a loving relationship with their own bodies, minds, and souls.

The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma by Bessel van der Kolk

Is he writing my biography?

Wait, am I in The Truman Show? Is this The Jennifer Show?

Coping takes its toll. For many children it is safer to hate themselves than to risk their relationship with their caregivers by expressing anger or by running away. As a result, abused children are likely to grow up believing that they are fundamentally unlovable; that was the only way their young minds could explain why they were treated so badly. They survive by denying, ignoring, and splitting off large chunks of reality: They forget the abuse; they suppress their rage or despair; they numb their physical sensations. If you were abused as a child, you are likely to have a childlike part living inside of you that is frozen in time, still holding fast to this kind of self-loathing and denial.

The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma by Bessel van der Kolk

Holy moly, that’s enough truth-telling.

Thank you for your book and your work, Bessel van der Kolk. I hope that it is okay to have quoted large chunks of your work here.

Now, before we move forward, I want all of us to take a moment to forgive our five-year-old selves. We were all doing the best we could.

Still, more than deserving forgiveness, our five-year-old selves deserve hugs—really good hugs where you fully feel and absorb the hug’s authentic gentleness, forgiveness, and kindness (right now, I’m writing this at the library and doing a mediocre job of keeping it together. Thankfully, this is a well-funded library and they have a full tissue box on the desk!).

Forgive yourself. Hug yourself. Kiss your shoulders.

Onward we go.

Spending a Lifetime with My Thoughts and Turning to “Number Three”

Through the “checking the facts” DBT exercise and Bessel van der Kolk, I realized that I have a lifelong history with these thoughts based on protection and survival. That is why they are automatic. That is why they feel so good (remember the hot cocoa, teddy bear, Linus’s blanket, inserted fuzzy thing?).

Nevertheless, our lifelong history doesn’t mean that my thoughts are true.

And, now, once more with feeling: Just because I have had these thoughts hundreds of times does not mean that they are true.

But, beyond thoughts as true, false, or neutral, sometimes we have thoughts that just keep popping up, and popping up, and popping up. And. Popping. Up.

They do this relentlessly for days, for weeks, for months, for a lifetime.

We have some options to play with here.

- You can label the thought as “thought” and let it pass.

- You can label the thought as “nonsense thought” or “false thought” and let it pass.

- You can invite the thought over for lemonade and cookies (sugar rush!!!). Then, kindly ask it to have a seat on the couch so that you can explore your lifelong history together.

Notes on Number Three

Number three, the third option outlined above, is where things get dark, dirty, smelly, and scary—even if you’ve laid out the lemonade and cookies. Because, ultimately, what good is sugar going to do when you’re diving headfirst into the maelstrom that is your childhood trauma?

Number three requires some sugar, unless you want to brag about how you’re on a ketogenic diet and you’re in full-on ketosis right now.

More seriously, number three requires unwavering bravery.

Number three requires an unwavering capacity to carry yourself with the utmost gentleness, kindness, forgiveness, and acceptance.

Number three requires bravery, gentleness, kindness, forgiveness, and acceptance because number three can feel like army crawling all by yourself through the thick, stinky muck that’s settled at the bottom of your mind’s pitch-dark sewer tunnels.

Number three is not a happy, smiley place to be, so proceed with utmost caution.

I highly recommend exploring number three with a mental health professional.

In fact, do not explore number three at all, unless you have access to a few of these things:

- A kind and accepting therapist who can gently guide you through the waves of fear, pain, and uncontrollable sobbing

- A kind and accepting significant other who you can talk to right now and who’s totally cool with being woken up at 3:07 AM to a gentle, yet persistent, tapping on their shoulder when panic ensues

- A kind and accepting mother who you can call right now and at 3:07 AM when panic ensues

- A kind and accepting sibling who you can call right now and, hopefully, you’re not reading this at 3:07 AM because siblings aren’t the ideal ones to call at 3:07 AM

- A kind and accepting friend who you can reach out to right now and ditto on the 3:07 AM caveat

- A complete and easily accessible safety plan

- Fail-safe ways to cope with the aftershocks of your exploration on your own because you got this and it ain’t no thang. Actually, it is a “thang”, but that’s what your fail-safe, personalized coping strategy is for.

Surviving Post-Exploration, A.K.A. Weathering the Shitstorm: Finding Coping Strategies that Actually Work

Alright, everyone, we are now on the other side of the shitstorm that is diving headfirst into our childhood trauma. Now, we get to watch Pride and Prejudice (the 2005 version starring Keira Knightley and Matthew Macfadyen, what else?) and—the best part—we get to watch it on repeat! That’s because when you bravely explore the darkest, dirtiest, smelliest, and scariest cavernous depths of your self-hatred and childhood trauma, your survival depends on bearing witness to the pure, blossoming love between Elizabeth Bennet and Fitzwilliam Darcy a few times, at the very least, even if their growing love to you is mere background noise filling your basement studio apartment as you sob on the cold floor holding fast to the one stuffed animal you own (thank you, Hairy) because you’re a grown adult.

Recently, I used Frozen and bread à la DBT’s “distract” skill to cope.

But, before, during, and after this coping session, I wondered to myself, “Does it make sense to cope by watching a movie and eating bread? Sure, it’s nice, easy, and maybe a little fun, but is this my best option? Is this the healthiest option?”

In reality, a movie and one baguette are effective, healthy ways of coping for me, especially when compared to the myriad of alternative approaches that I, or anyone for that matter, could turn to cope with the ups and downs of life:

- Panic attacks

- Insomnia

- Depression

- Suicidality

- Reckless and excessive use of money, work, food, avoidance, exercise, TV, movies, gossiping, sleep, drugs, alcohol, sex, religion, gambling, partying, etc.

Coping strategies are personal. Learning about someone’s coping strategies is almost like reading their diary or peeking inside of their underwear drawer. While a movie and a baguette are effective and healthy for me, they may be ineffective and unhealthy for someone else. Building your portfolio of coping strategies is a personal process of experimentation, addition, and subtraction. For example, Frozen made the cut, but Inside Out was a non-starter because, despite how good this movie is, my sadness became unbearable while watching Riley’s personality disintegrate. It hit too close to home for me, and I accept that.

My coping strategy extends well beyond Frozen, baguette (singular), and avoiding Inside Out, however. When shit really feels like it’s about to hit the fan, I pull out, in no particular order, all of the stops:

- The aforementioned Pride and Prejudice (2005), triple screening

- Warm fudge brownies

- Paced deep breathing

- Dancing, of late to “Human Right“, because dancing is a human right

- Naps, after setting a 30-minute timer

- Handwashing dishes

- Writing

- Smelling new books

- Folding laundry

- Reading Reasons to Stay Alive by Matt Haig

- Walking by the river

- Being kind, accepting, and gentle with myself

- Cross country skiing, especially when it feels like dancing

- Grocery store tiramisu

- Hiking, especially on a glittery, snowy trail

- Listening to podcasts (She’s All Fat) and audiobooks

- Singing, of late “Human Right“, because singing is also a human right

- Scrubbing my toilet

- Drinking a single glass of Malbec

- Studying statistics and economics

- John Oliver (from YouTube because, unfortunately, I do not live with him, and therefore, cannot wake him up at 3:07 AM when panic ensues)

- Alain de Botton (also YouTube)

- Stephen Colbert (also YouTube…and what’s the deal with all of these white guys in my coping strategy?)

- Chocolate cake

- Journaling

- Crying, after setting a 5-10 minute timer and locating Hairy

- ASMR videos on YouTube

- Talking to my mom and/or brother

- Salt and vinegar potato chips

- Saying affirmations in the mirror, of late “You are doing the best you can. You are good enough.” And, “You can do this. You are doing this.”

- Jumping Janes (Janes to atone for having so many white males in my coping strategy)

- The aforementioned bread, with or without the aforementioned Frozen

- General tidying

- Cooking, of late “Spiced Chickpea Stew With Coconut and Turmeric“

- Lighting candles and incense

I go and I go and I go until I’m through it.

Sometimes, the post-exploration recovery period takes 30 minutes. Other times, it can take three days, a week, longer even. The duration depends entirely on how real shit got while exploring those pitch-dark sewer tunnels.

Rebuilding Myself

This past weekend, I spent some time on number three. And post-recovery (I’m very, very serious about the need for a post-exploration recovery period), I walked away wanting to rebuild my body armor, and not from self-hatred, like I used when I was five-years-old, but from something else.

I decided that I want to rebuild my body armor from gentleness, forgiveness, and kindness—whatever beautiful, ethereal material that is.

But, let’s zoom out a bit more. In reality, “body armor” doesn’t quite describe what I really want to build.

It’s more that I want to build a deliciously comfy king-size bed with all of the pillow, sheet, and blanket fixings so that I feel like I’m resting and sleeping inside of what a cumulus cloud looks like.

No.

As delicious as that cumulus cloud bed sounds, it’s still not quite right. And, what’s more, I don’t think “build” hits the spot either.

Let’s try again.

It’s more that I want to embody the gentleness, forgiveness, and kindness of that really good hug that I desperately needed when I was five-years-old.

Yes.

That’s it.

Image: Krista Mangulsone

Thank you for taking this journey with me.

Now, let’s take a breath and take a break.